This presentation looks at the various ways in which the

Nizamuddin shrine and its adjacent structures have been

illustrated over the centuries, whether to depict the complex as

part of Delhi’s ancient heritage or a sacred space for the

devotees. How do the earliest colonial images – meant to

showcase Delhi’s built heritage – contrast with popular images

and devotional literature about the shrine produced by a

mass-based print industry meant for the pilgrims’ consumption?

This presentation looks at the various ways in which the

Nizamuddin shrine and its adjacent structures have been

illustrated over the centuries, whether to depict the complex as

part of Delhi’s ancient heritage or a sacred space for the

devotees. How do the earliest colonial images – meant to

showcase Delhi’s built heritage – contrast with popular images

and devotional literature about the shrine produced by a

mass-based print industry meant for the pilgrims’ consumption?

Early images/descriptions about the Nizamuddin Shrine

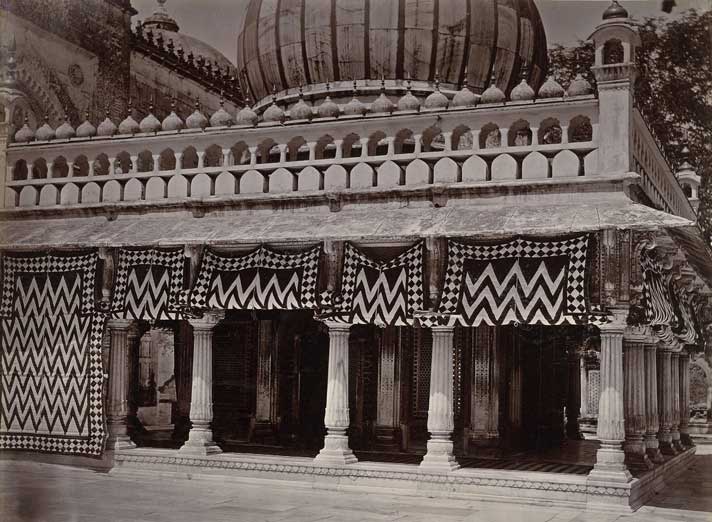

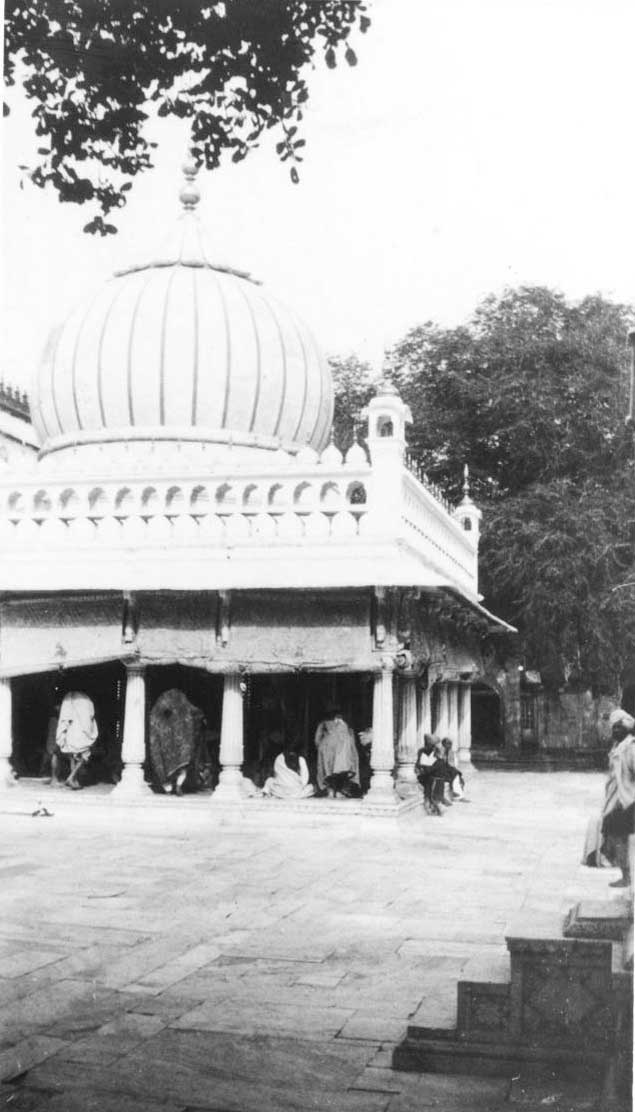

The present tomb of Nizamuddin is basically a small square

chamber with narrow verandahs on all four sides. The walls of

the chamber consist mostly of jali or screens and the roof is

surmounted by a white marble dome with vertical black stripes.

The present tomb of Nizamuddin is basically a small square

chamber with narrow verandahs on all four sides. The walls of

the chamber consist mostly of jali or screens and the roof is

surmounted by a white marble dome with vertical black stripes.

Actually, Nizamuddin’s last residence or spiritual retreat was

not where his tomb is located.

Actually, Nizamuddin’s last residence or spiritual retreat was

not where his tomb is located.

Rather it was situated about a kilometre away from the present tomb – a place known as the chilla khana, at the extreme northeast corner of the charbagh (square garden) that surrounds the Mughal emperor Humayun’s tomb.[1] In fact, the location of Humayun’s tomb may have been chosen deliberately to exist between the residence and the mausoleum of Nizamuddin Aulia for the sacrality of the space. No wonder then that later Mughal kings such as Shahjahan and even Akbar, whenever they visited Delhi from Agra (their capital), made it a point to make a pilgrimage to the tombs of Humayun (their ancestor) as well as saint Nizamuddin, who they considered their spiritual master, in a ritual-like movement. [2] Even though his initial tomb and nearby jamat khana (mosque) was built during the Firuz Shah’s rule, many more additions (such as sandstone and marble screens) and renovations carried on at the mausoleum of Nizamuddin Aulia especially during the Mughal period. Besides the repairs made during Babur’s and Humayun’s period, Akbar’s governor in Delhi, Shihabuddin (in 1561-62) and a nobleman Faridun Khan (the following year) helped build the tomb as it mostly exists today.

Many more repairs and new graves continued to be added until the middle of 20th century.[3] But the next important and revered grave in the compound is definitely that of Amir Khusrau Dehlavi, a friend and disciple of the saint as well as a courtier in Delhi Sultanate.

Despite many textual accounts about the popularity, material

culture and spiritual powers of the shrine, hardly any accurate

image of its buildings were available until the middle of 19th

century when some European travellers either produced or

commissioned its drawings along with those of other famous

heritage buildings of Delhi for documentation purposes. Almost

any traveller to Delhi on a short sojourn was bound to visit the

customary buildings: Humayun’s tomb, Qutab minar, Nizamuddin

dargah, (Shahjahan’s) Jama masjid and so on. And these are the

buildings that also get illustrated in most travel accounts or

photo albums, even though the list of Delhi's surviving heritage

buildings ran into thousands (according to Sir Syed Ahmed Khan's

1847 listing).

[4]

Despite many textual accounts about the popularity, material

culture and spiritual powers of the shrine, hardly any accurate

image of its buildings were available until the middle of 19th

century when some European travellers either produced or

commissioned its drawings along with those of other famous

heritage buildings of Delhi for documentation purposes. Almost

any traveller to Delhi on a short sojourn was bound to visit the

customary buildings: Humayun’s tomb, Qutab minar, Nizamuddin

dargah, (Shahjahan’s) Jama masjid and so on. And these are the

buildings that also get illustrated in most travel accounts or

photo albums, even though the list of Delhi's surviving heritage

buildings ran into thousands (according to Sir Syed Ahmed Khan's

1847 listing).

[4]

For this report however, I would like to focus on a few of these available images of Nizamuddin shrine to see what purposes they may have served and what narratives or versions of historical facts accompanied these images.

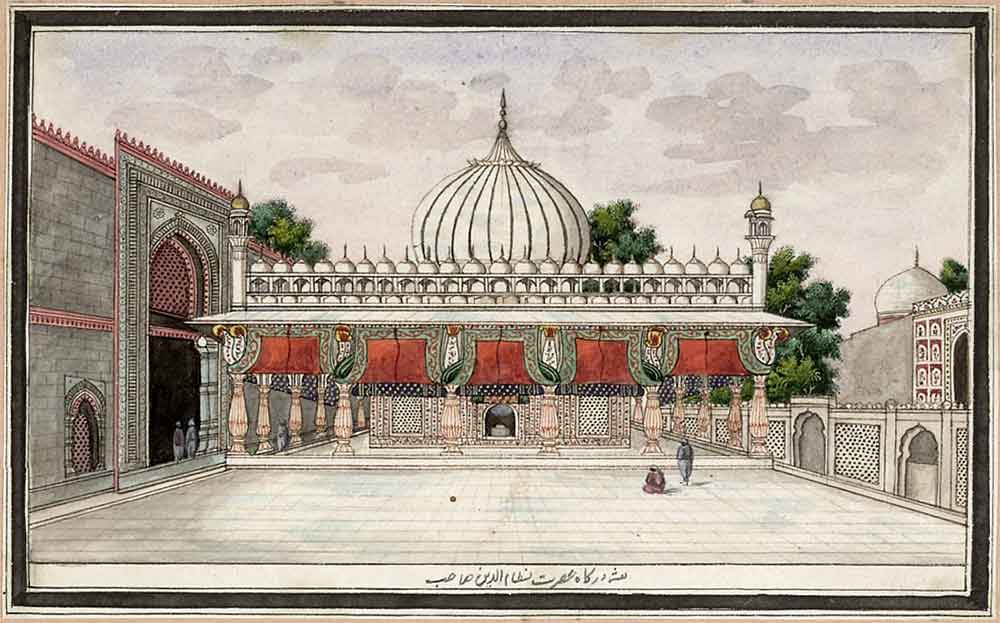

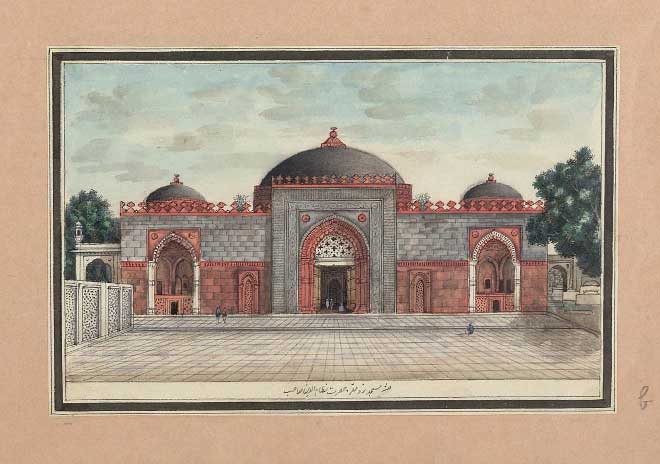

We know that 19th century already had a well-developed print culture in India with books, pamphlets and decorative images (many in colour) being produced in large number for the consumption of Europeans as well Indians. Besides Syed Ahmed’s own book Asar-us Sanadid which has simple line drawings of Nizamuddin mausoleum and other adjacent buildings, the most fascinating near-contemporary visual source is an album called 'Reminiscences of Imperial Delhi’, containing 89 folios with about 130 paintings of the Mughal and pre-Mughal monuments of Delhi, and a text in English written by Sir Thomas Metcalfe (1795-1853), the Governor-General’s Agent at the imperial court.[5] The paintings seem to have been drawn in ink and colours on paper by a local artist whose signature and the title of the image appear in Urdu at the bottom. Most illustrated pages have two paintings and a detailed text on the facing page. The page that shows the shrine of Nizamuddin also has the image of the jamat-khana mosque near it.

The most fascinating part is that in order to clearly reveal the

façade of the mosque, the artist has taken the liberty of

removing the main enclosure of Nizamuddin’s tomb from the view

and drawn only a blank courtyard in the front with receding

checkerboard floor! Not only that an ordinary observer of such

an image would not be able to recognize this building (they have

never witnessed the mosque in this unhindered manner - not even

when it was constructed, since the tomb of Nizamuddin may have

always obstructed this view), but the very act of the “removal”

of saint’s tomb from an illustration could be seen by the

ordinary devotees as sacrilegious, even though its original

artist was a Muslim. For a devotee, as we shall see later, the

presence of the saint is much more important than mere buildings

or archetypes, even if the former disrupts the symmetry of a

mosque building. But the commissioning of such an image was

probably Metcalf’s way of showing (and seeing) a beautiful

monument in its full splendour – a sort of a dissection of a

building complex that goes even beyond the scope of photography

in its depiction of realism.

The most fascinating part is that in order to clearly reveal the

façade of the mosque, the artist has taken the liberty of

removing the main enclosure of Nizamuddin’s tomb from the view

and drawn only a blank courtyard in the front with receding

checkerboard floor! Not only that an ordinary observer of such

an image would not be able to recognize this building (they have

never witnessed the mosque in this unhindered manner - not even

when it was constructed, since the tomb of Nizamuddin may have

always obstructed this view), but the very act of the “removal”

of saint’s tomb from an illustration could be seen by the

ordinary devotees as sacrilegious, even though its original

artist was a Muslim. For a devotee, as we shall see later, the

presence of the saint is much more important than mere buildings

or archetypes, even if the former disrupts the symmetry of a

mosque building. But the commissioning of such an image was

probably Metcalf’s way of showing (and seeing) a beautiful

monument in its full splendour – a sort of a dissection of a

building complex that goes even beyond the scope of photography

in its depiction of realism.

Even the angle (and distance) from which the main image of Nizamuddin tomb is seen looks a bit imaginary – the artist may have had to remove (in his mind) a screen wall and another grave in order to see the mausoleum from such an angle. This also makes us wonder what other details of the shrine (including the existence of visitors) the artist might have ignored or avoided in these images.

Metcalf’s texts provide some introductory details about the monument and the life of the saint, but not all of it historically accurate. According to him, for instance, Nizamuddin “was born at Ghuznee in Afghanistan, about the year AD 1237, provided the date of the Mahomedan era be correct viz. in 635 of the Hegirah or the year of the flight of the Prophet Mahomet.” [6] However, we know today that Nizamuddin was born in Badayun in the year 1242. [7] Similarly, Metcalf attributes the construction of jamat-khana mosque in 1325 to Khizr Khan (the son of Alauddin Khalji) as is a popularly known, even though Khizr Khan has probably died many years before Nizamuddin’s death. [8] The text also mentions the accidental death of the king Ghayasuddin Tughlaq a few miles outside Delhi as he was approaching to eliminate Nizamuddin Aulia.

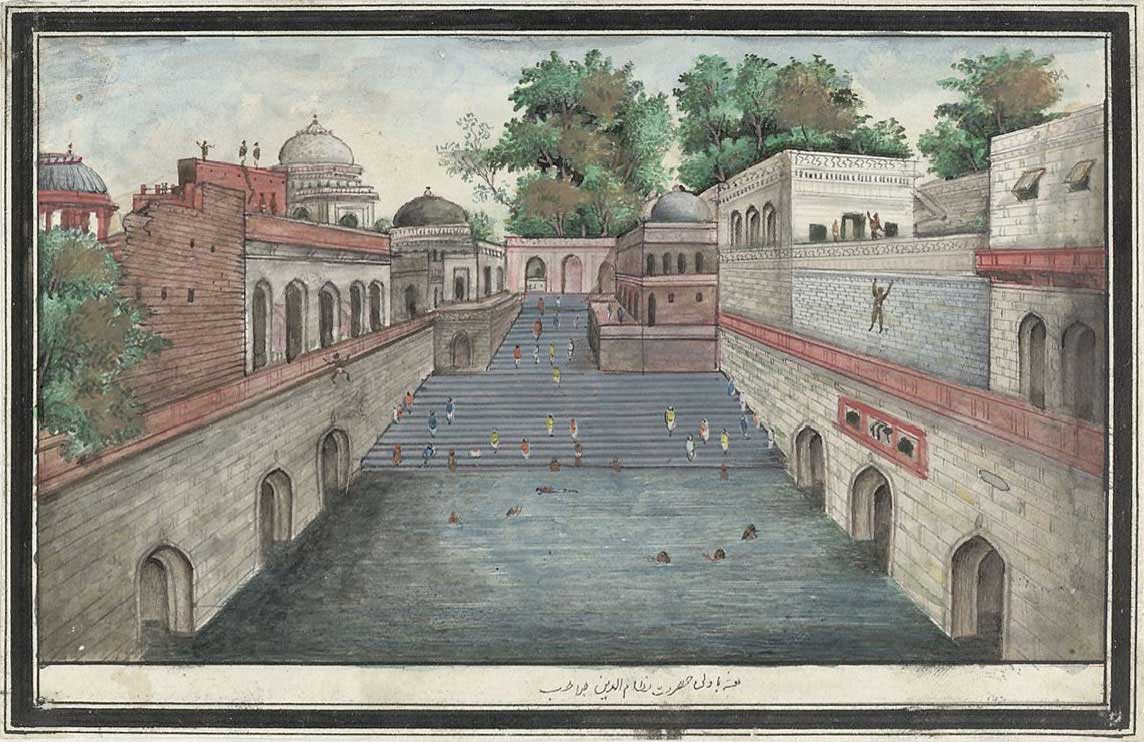

Metcalf’s album has the illustrations (or naqshas – diagrams) of other nearby buildings such as the baoli (step-well), the tombs of Amir Khusrau and later Mughal family members, including a building known as the chaunsath khamba (64-pillars).

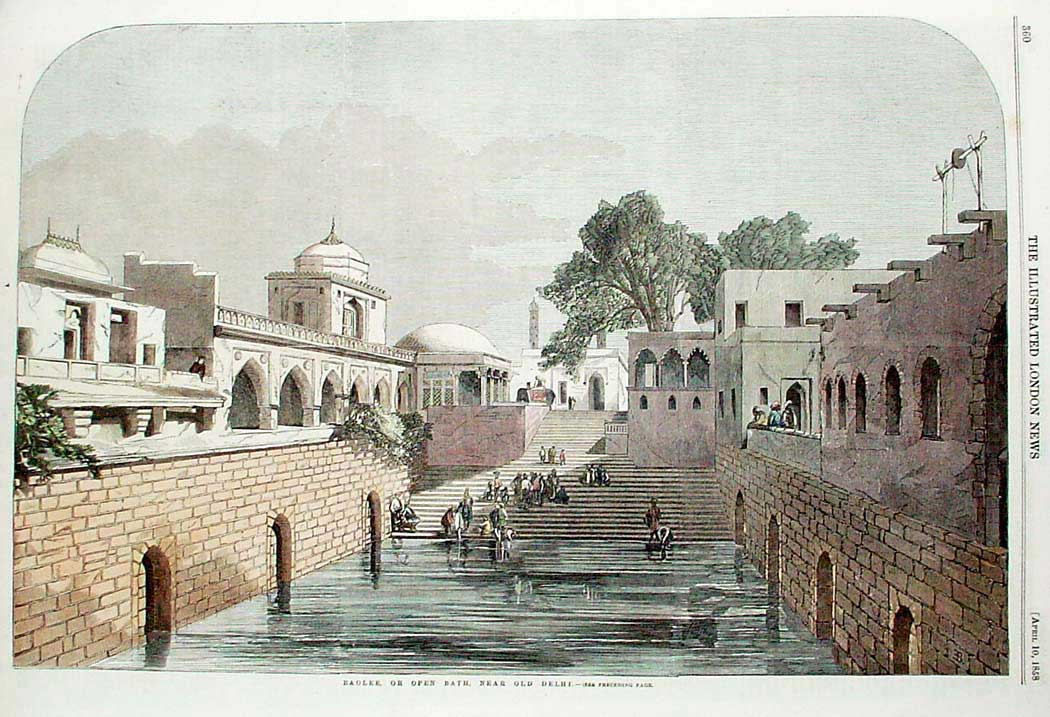

Among these, the image of baoli situated near the northern gate

of the shrine is of utmost significance to us since it has

served a variety of symbolic and practical purposes besides

simply providing water for ablution of the visitors. Its

construction itself is known to be an act of defiance and a

demonstration of spiritual power from the saint, since

Ghayasuddin Tughlaq was against its construction as he needed

workers for the construction of his own fort (Tughlaqabad). When

the workers started constructing the baoli at night using oil

lamps, the king stopped the supply of oil for them. But it is

claimed that Nizamuddin’s disciple Nasiruddin (who was

supervising the baoli work) miraculously used water to light the

lamps and continued the work. This miracle is also attributed

for his title Chiragh-Dehli (the lamp of Delhi).

Among these, the image of baoli situated near the northern gate

of the shrine is of utmost significance to us since it has

served a variety of symbolic and practical purposes besides

simply providing water for ablution of the visitors. Its

construction itself is known to be an act of defiance and a

demonstration of spiritual power from the saint, since

Ghayasuddin Tughlaq was against its construction as he needed

workers for the construction of his own fort (Tughlaqabad). When

the workers started constructing the baoli at night using oil

lamps, the king stopped the supply of oil for them. But it is

claimed that Nizamuddin’s disciple Nasiruddin (who was

supervising the baoli work) miraculously used water to light the

lamps and continued the work. This miracle is also attributed

for his title Chiragh-Dehli (the lamp of Delhi).

The baoli, it is claimed, had about seven ground water sources or streams, each tasting differently according to the local lure, and is today the only active stepwell in Delhi (among many).

The casual visitors not only used it for ablutions before the

five prayers of the day but also washed clothes and took bath in

it. Occasional male visitors or pilgrims used to dive into it

and swim since it has high walls or structures around it to give

a thrill of diving. Many images (drawings and photographs) from

19th and early 20th centuries depict occasional divers jumping

or about to jump from high-rise structures.

Thus, according to Metcalf, the baoli “is much resorted to by

travellers, to witness the feats of divers who are located at

the place, and jump from a considerable height into the

reservoir.” On special occasions such as the urs (death

anniversary fete) of the saint, hundreds of visitors from

far-away neighbourhoods of Delhi held competitions of diving in

the baoli. One of the earliest illustrations of the Nizamuddin

baoli (1802) was made by engraver Thomas Daniell (1749-1840),

featured in Thomas and William Daniell's 'Oriental Scenery'.[9]

The coloured aquatint image shows a couple of women filling or

using the well’s water - Daniells also saw small boys

dive into the water to retrieve coins, as they still do.

Thus, according to Metcalf, the baoli “is much resorted to by

travellers, to witness the feats of divers who are located at

the place, and jump from a considerable height into the

reservoir.” On special occasions such as the urs (death

anniversary fete) of the saint, hundreds of visitors from

far-away neighbourhoods of Delhi held competitions of diving in

the baoli. One of the earliest illustrations of the Nizamuddin

baoli (1802) was made by engraver Thomas Daniell (1749-1840),

featured in Thomas and William Daniell's 'Oriental Scenery'.[9]

The coloured aquatint image shows a couple of women filling or

using the well’s water - Daniells also saw small boys

dive into the water to retrieve coins, as they still do.

Visitors not only threw coins into the baoli to get their wishes come true (as they do even in Hindu devotional spaces, such as sacred rivers or ponds), they even drank or tasted its water considering it sacred. It must have been a busy and important landmark of Delhi in order to get noticed by so many visitors. The Illustrated London News of April 10, 1858, printed a colour drawing of the "Baolee or open bath near old Delhi" where many people seem to be using its water although none diving. The symmetry and receding perspective of the baoli along with the Islamic arches and domes around it somehow made it look like an ideal picture of living heritage.

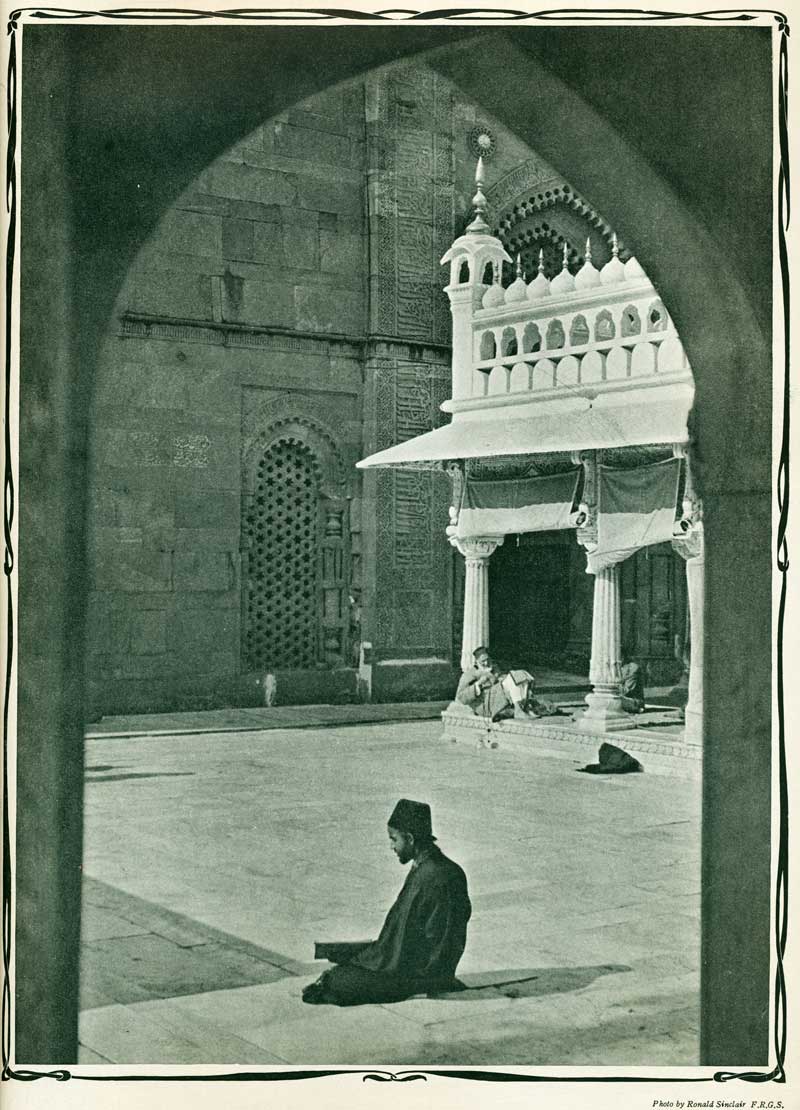

Photographs, postcards and posters

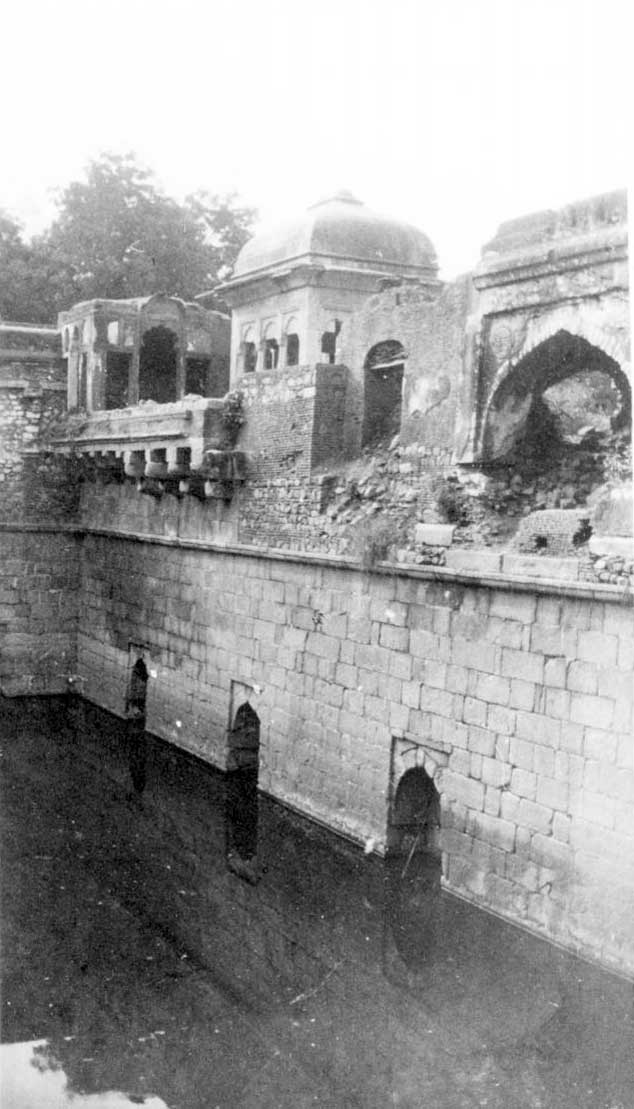

After the illustrations from the works of Daniells, Syed Ahmed

and Metcalf, we start getting some photographs of the Nizamuddin

shrine taken by different visitors. It should be noted that this

is a crucial juncture of history in terms of how the buildings

and the general landscape of Delhi looked like before and after.

After the illustrations from the works of Daniells, Syed Ahmed

and Metcalf, we start getting some photographs of the Nizamuddin

shrine taken by different visitors. It should be noted that this

is a crucial juncture of history in terms of how the buildings

and the general landscape of Delhi looked like before and after.

While most images documented before 1857 reveal a serenity and

order of life in Delhi, the illustrations and photographs taken

immediately after the turbulent events of 1857 rebellion show

almost every building in a state of disrepair and ruin. Samuel

Bourne who established photography studios in Shimla and

Calcutta (as Bourne and Shepherd) took several panoramic

photographs in Delhi around 1860, including at least two that

show the landscape of ruins around Humayun’s tomb and

Nizamuddin shrine.

The same year, John Edward Saché also took pictures in the

shrine for his 'Album of Indian Views', but did not include an

image of the stepwell.

The same year, John Edward Saché also took pictures in the

shrine for his 'Album of Indian Views', but did not include an

image of the stepwell.

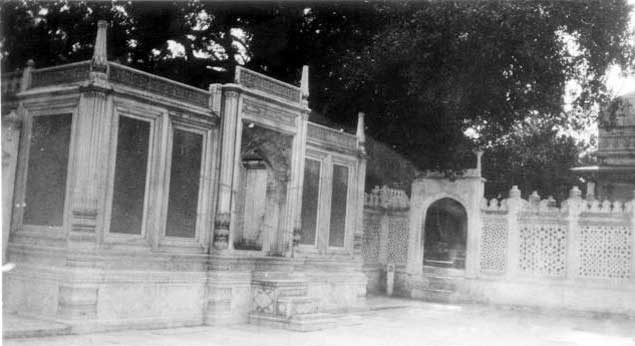

A very clear and close-up photograph of the Nizamuddin tomb,

taken by G.W. Lawrie and Company in 1895 for the Macnabb

Collection, shows cloth curtains with attractive patterns

covering the verandas of the chamber.

A very clear and close-up photograph of the Nizamuddin tomb,

taken by G.W. Lawrie and Company in 1895 for the Macnabb

Collection, shows cloth curtains with attractive patterns

covering the verandas of the chamber.

Such temporary additions to the built structures allow us to see

the embellishments the rich pilgrims used to occasionally gift

for the shrine, as they still do. Many of these images

(especially in the British Library collection) carry very

similar information in the captions (such as attributing the

construction of the tomb to Faridun Khan and so on). However,

this photograph provides an additional detail about the inside

of the chamber: “The tomb of the saint in the interior is

enclosed by a marble rail and covered with a canopy of mother of

pearl provided by Shaikh Farid Bukhari in 1608-09.” The same

wooden canopy is probably still preserved in the chamber (as

seen by the author in 2010), although some of the pearl

decoration missing.

Such temporary additions to the built structures allow us to see

the embellishments the rich pilgrims used to occasionally gift

for the shrine, as they still do. Many of these images

(especially in the British Library collection) carry very

similar information in the captions (such as attributing the

construction of the tomb to Faridun Khan and so on). However,

this photograph provides an additional detail about the inside

of the chamber: “The tomb of the saint in the interior is

enclosed by a marble rail and covered with a canopy of mother of

pearl provided by Shaikh Farid Bukhari in 1608-09.” The same

wooden canopy is probably still preserved in the chamber (as

seen by the author in 2010), although some of the pearl

decoration missing.

Early 20th century saw the visits of the famed British woman

photographer and author Gertrude Bell in Delhi who took many

photos (such as on 9th January 1903) of the Nizamuddin shrine

complex from angles that reflect a realism not seen in the

previous illustrations. In general, Gertrude’s prolific

photographs capture the casual life apart from the buildings.

She also covered the baoli in a tall vertical photograph

depicting one of its sides.

[10]

Early 20th century saw the visits of the famed British woman

photographer and author Gertrude Bell in Delhi who took many

photos (such as on 9th January 1903) of the Nizamuddin shrine

complex from angles that reflect a realism not seen in the

previous illustrations. In general, Gertrude’s prolific

photographs capture the casual life apart from the buildings.

She also covered the baoli in a tall vertical photograph

depicting one of its sides.

[10]

One finds at least one photograph of the baoli taken in early

1900s by Merl La Voy, an American photographer and traveller.

One finds at least one photograph of the baoli taken in early

1900s by Merl La Voy, an American photographer and traveller.

At the end of 19th century, as more and more images were being

used for commercial purposes such as posters, calendars, and

most importantly, postcards, the illustrations of famous

buildings or shrines also got mass produced.

At the end of 19th century, as more and more images were being

used for commercial purposes such as posters, calendars, and

most importantly, postcards, the illustrations of famous

buildings or shrines also got mass produced.

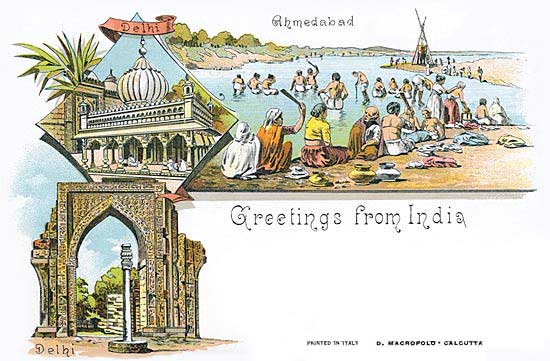

In the German-style postcard series of

Gruss Aus (Greetings from), one finds one 1900 postcard

titled “Greetings from India”

In the German-style postcard series of

Gruss Aus (Greetings from), one finds one 1900 postcard

titled “Greetings from India”

that makes a collage of three illustrations: (1) washerwomen on

a riverfront in Ahmedabad, (2) Delhi’s Nizamuddin shrine and (3)

the Ashokan pillar at Mehrauli, besides blank space for a short

message.

[11]

that makes a collage of three illustrations: (1) washerwomen on

a riverfront in Ahmedabad, (2) Delhi’s Nizamuddin shrine and (3)

the Ashokan pillar at Mehrauli, besides blank space for a short

message.

[11]

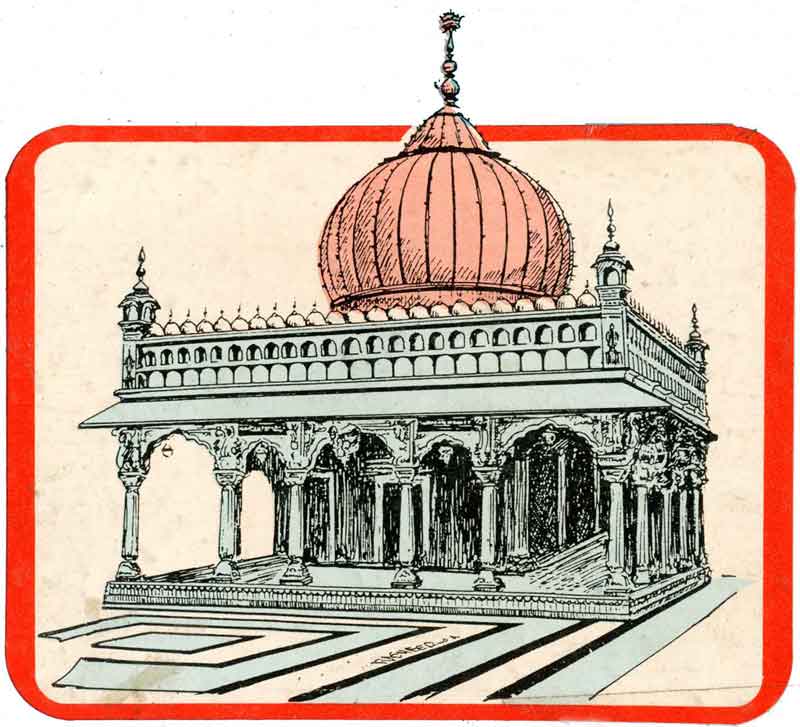

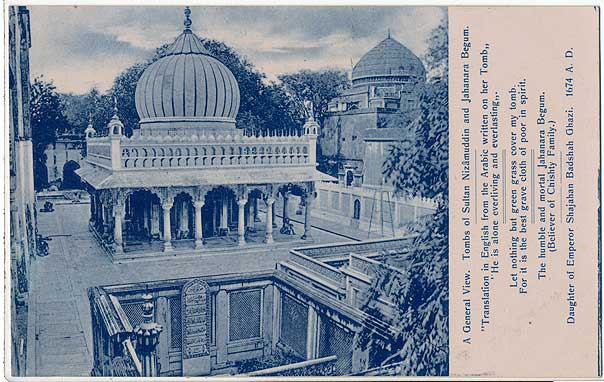

More prominent commercial examples of Nizamuddin shrine’s image

released on a postcard was from H.A.Mirza (circa 1910),

More prominent commercial examples of Nizamuddin shrine’s image

released on a postcard was from H.A.Mirza (circa 1910),

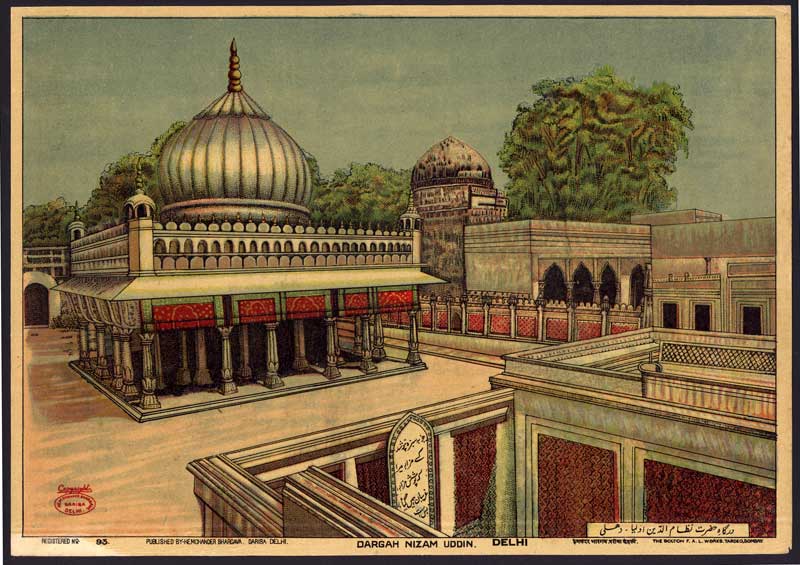

and a very similar image on a small poster from Hemchadar

Bhargava (circa 1920), both from Chandni Chowk in Delhi.

and a very similar image on a small poster from Hemchadar

Bhargava (circa 1920), both from Chandni Chowk in Delhi.

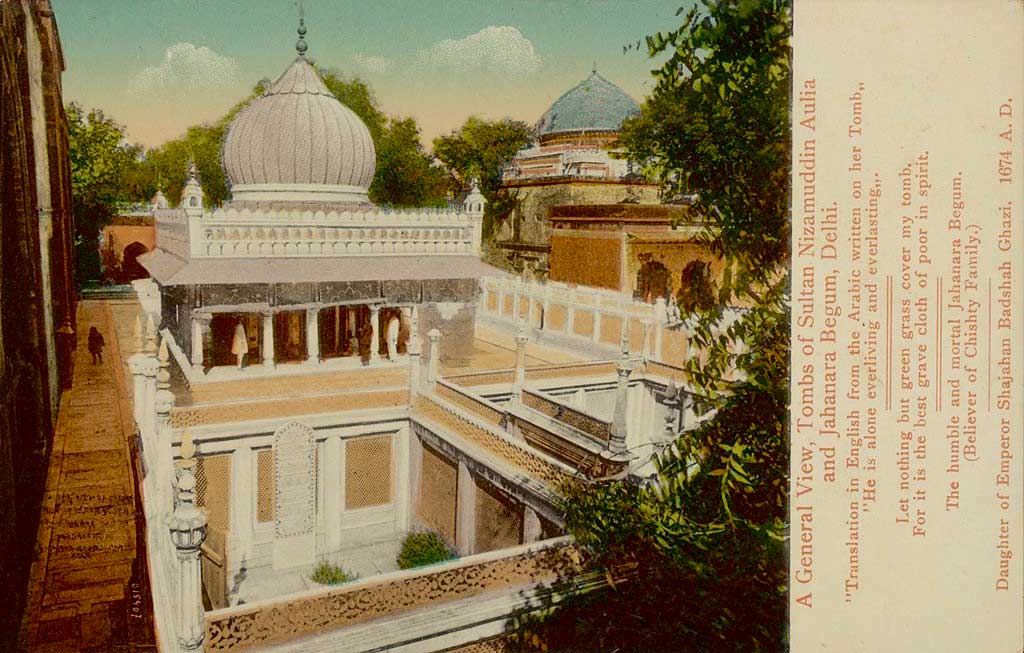

Both Mirza’s and Bhargava’s images have been taken from the

extreme southwest corner of the courtyard a little above the

marble grave of princess Jahanara, the daughter of Mughal king

Shahjahan. In fact Mirza took another photo from almost the same

angle a little later in a coloured or colour-tinted version, in

both cases providing text captions on a white band on the right

corner of the image,

Both Mirza’s and Bhargava’s images have been taken from the

extreme southwest corner of the courtyard a little above the

marble grave of princess Jahanara, the daughter of Mughal king

Shahjahan. In fact Mirza took another photo from almost the same

angle a little later in a coloured or colour-tinted version, in

both cases providing text captions on a white band on the right

corner of the image,

which introduce the tombs of Nizamuddin as well as Jahanara by

providing the English translation of the Persian text inscribed

on her gravestone.[12]

which introduce the tombs of Nizamuddin as well as Jahanara by

providing the English translation of the Persian text inscribed

on her gravestone.[12]

Bhargava might have copied his poster illustration from Mirza’s photo postcard (as was the trend among publishers such as Ravi Varma Press and Bhargava), [13] but only captions it as the tomb of Nizamuddin, although vividly highlighting the gravestone of Jahanara by making its Persian text almost readable.

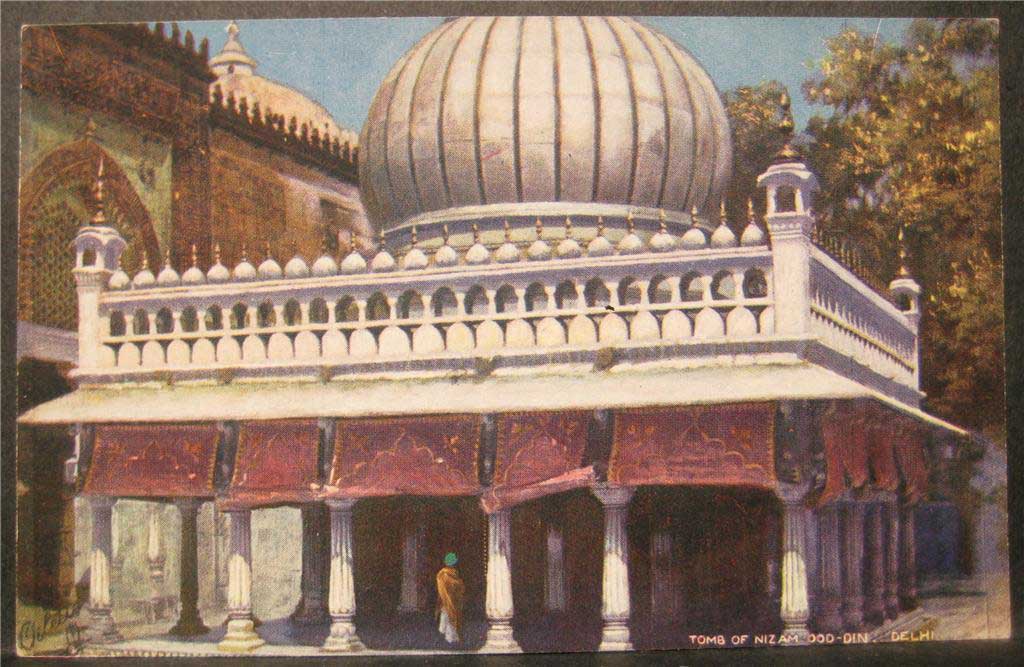

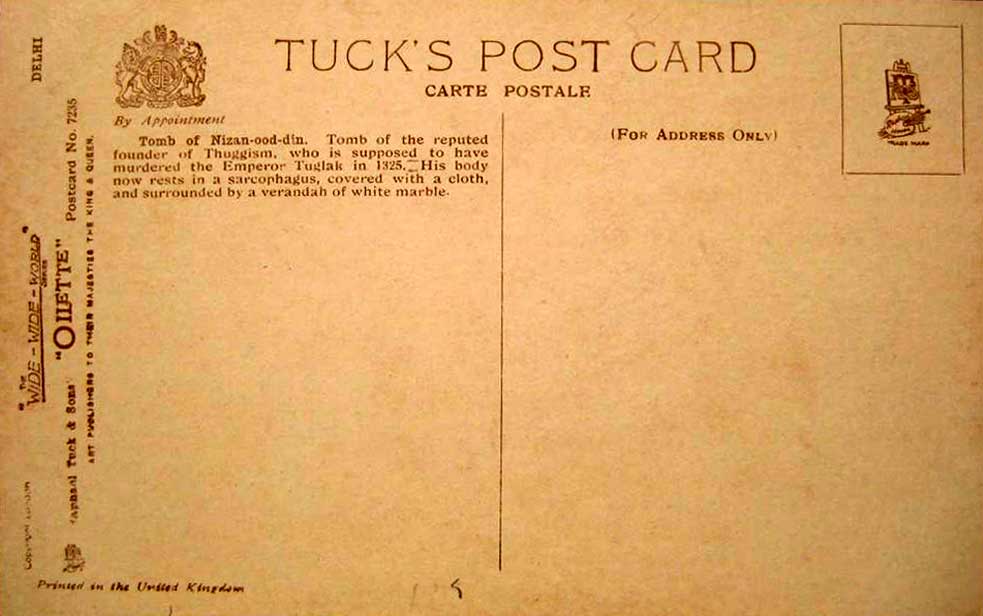

Interestingly, in its colour scheme and design on the curtains

on the tomb, the Bhargava image seems to have been inspired by

another contemporary postcard image of the shrine. The postcard

company Raphael Tuck & Sons (based in Lahore, Calcutta and

London)

came up with a coloured or colour-tinted photograph of

Nizamuddin tomb on its postcard in late 1920s, where the tomb’s

curtains are very similar to what appears in the Bhargava image.

But the most intriguing part of Tuck’s postcard is its caption

at the back: “Tomb of Nizan-ood-din. Tomb of the reputed founder

of Thuggism,

came up with a coloured or colour-tinted photograph of

Nizamuddin tomb on its postcard in late 1920s, where the tomb’s

curtains are very similar to what appears in the Bhargava image.

But the most intriguing part of Tuck’s postcard is its caption

at the back: “Tomb of Nizan-ood-din. Tomb of the reputed founder

of Thuggism,

who is supposed to have murdered the Emperor Tuglak in 1325. His

body now rests in a sarcophagus, covered with a cloth, and

surrounded by a verandah of white marble.”

who is supposed to have murdered the Emperor Tuglak in 1325. His

body now rests in a sarcophagus, covered with a cloth, and

surrounded by a verandah of white marble.”

It’s difficult to say if the author of this statement is misinformed or deliberately referring to the saint’s involvement in the Emperor’s death (although connecting the saint with thuggism would be found ludicrous by anyone – even the contemporary kings who were most antagonistic to his presence swore by his spiritual powers).

According to Khaliq Nizami, there is a lobby of European

historians who have floated the story of Nizamuddin’s direct

involvement in Tughlaq’s death, which is impossible by any

means.

[14]

In any case, the caption texts in most history/heritage-related

postcards produced by Tucks (or even other publishers) has been

found to be rather sketchy and often incorrect.

In any case, the caption texts in most history/heritage-related

postcards produced by Tucks (or even other publishers) has been

found to be rather sketchy and often incorrect.

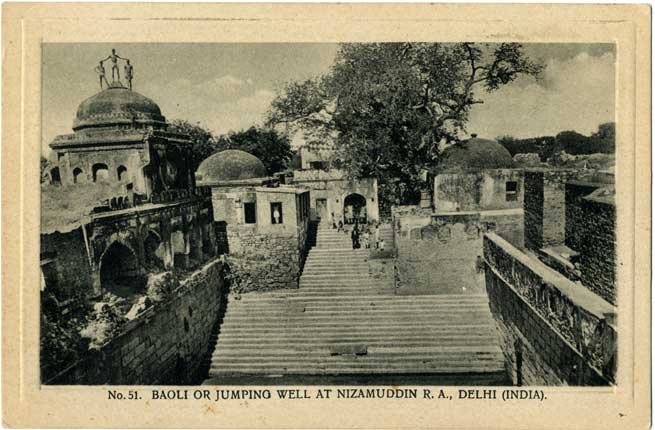

Although its image was never used as a poster, the Nizamuddin

baoli appears in some B&W postcards by H.A. Mirza and Lal

Chand and Sons, both of whom title it as the “Jumping well of

dargah Nizamuddin” indicating its role as a place for adventure

and showmanship, as if the feats of diving into it were worth a

watch for the visitors – the divers atop precarious domes seem

to be posing for the photograph.

Although its image was never used as a poster, the Nizamuddin

baoli appears in some B&W postcards by H.A. Mirza and Lal

Chand and Sons, both of whom title it as the “Jumping well of

dargah Nizamuddin” indicating its role as a place for adventure

and showmanship, as if the feats of diving into it were worth a

watch for the visitors – the divers atop precarious domes seem

to be posing for the photograph.

The caption text on one of Mirza’s baoli postcards mentions the saint having “blessed the water which worked like oil to lit the lamp” referring to Nizamuddin’s stand-off with the king during the construction of stepwell, thus not only elevating the spiritual value of an image of such a ruin but also making the lore available to many outsiders who may have received this postcard. The perforations at one end of the postcards reveal that they were sold in albums showing other views of Delhi’s heritage locations.

Almost all these publishers also printed images of other Muslim shrines such as those of Salim Chishti (Fatehpur Sikri), Moinuddin Chishti (Ajmer), Sabir Pak (Kaliyar), and some in south India. Besides on the postcards, the shrines, especially that of Nizamuddin, have also been depicted as sites of heritage in early 20th century magazines published for the English readers. The Times of India Annual (of 1935) features a couple of such images of the shrine.

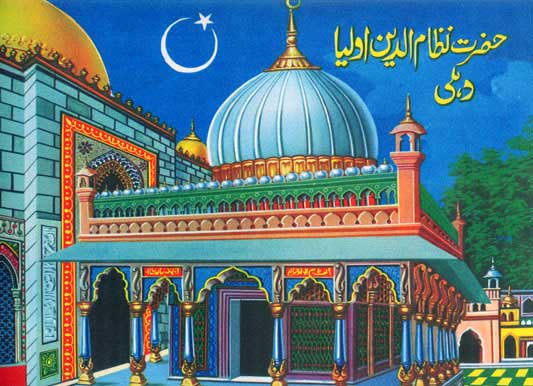

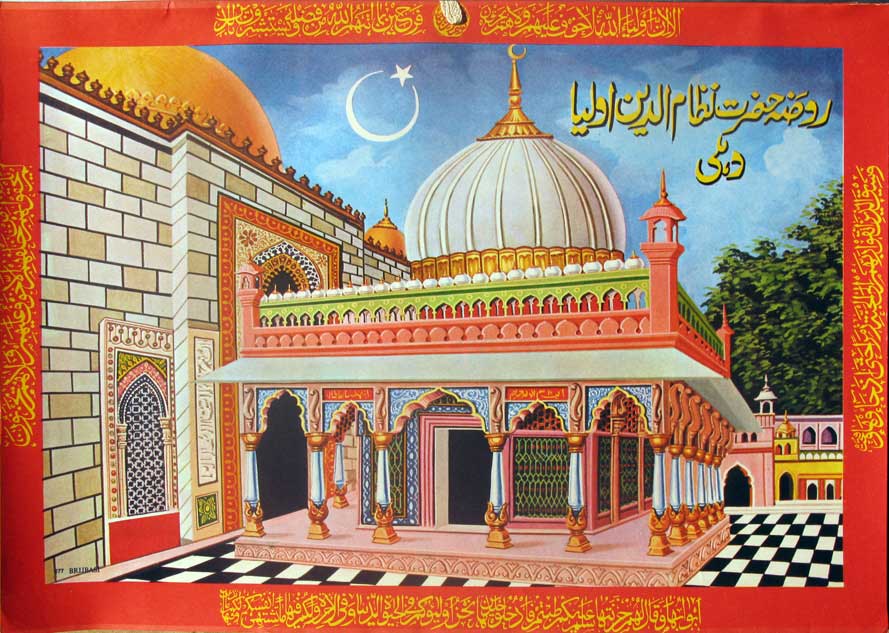

While discussing the shrines as heritage buildings one should

not forget that these were ultimately being visited by religious

devotees some of whom would buy image-based mementos during

their pilgrimage. While the postcards may not have served the

purpose of devotional gaze, the pilgrims may have certainly

purchased the coloured posters of a site like Nizamuddin dargah.

While discussing the shrines as heritage buildings one should

not forget that these were ultimately being visited by religious

devotees some of whom would buy image-based mementos during

their pilgrimage. While the postcards may not have served the

purpose of devotional gaze, the pilgrims may have certainly

purchased the coloured posters of a site like Nizamuddin dargah.

This is especially true since Bhargava was already producing a

large variety of Islamic posters in the early 20th century

depicting images of Islamic monuments and shrines including

Mecca, Karbala, and Jama masjid, besides hundreds of prints of

Islamic/Arabic calligraphy with floral borders. But some of

these cannot be strictly classified as Muslim devotional – many

also had images of heritage buildings. Other early publishers

who produced such images are Ravi Varma Press, Anant Shivaji

Desai and PPC – all based in Bombay. They may have had an eye on

the devotional market, but some of their images of heritage

buildings served for both religious as well as secular use.

This is especially true since Bhargava was already producing a

large variety of Islamic posters in the early 20th century

depicting images of Islamic monuments and shrines including

Mecca, Karbala, and Jama masjid, besides hundreds of prints of

Islamic/Arabic calligraphy with floral borders. But some of

these cannot be strictly classified as Muslim devotional – many

also had images of heritage buildings. Other early publishers

who produced such images are Ravi Varma Press, Anant Shivaji

Desai and PPC – all based in Bombay. They may have had an eye on

the devotional market, but some of their images of heritage

buildings served for both religious as well as secular use.

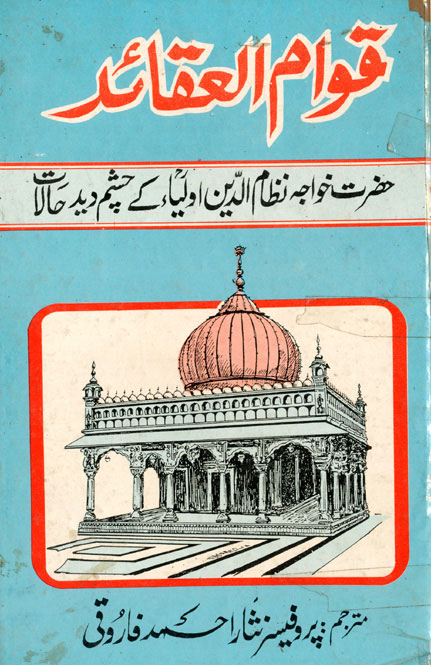

Not too many varieties of devotional posters depicting Nizamuddin shrine were made available in 20th century as compared to other shrines such as Ajmer. In fact, only one standard image of Nizamuddin by Brijbasi has remained in circulation with slight variations for decades. One more popular poster shows an assembly of six Chishti Sufis including Nizamuddin Aulia sitting besides inset pictures of their tombs. Some chapbooks or biographies of the saint available outside the shrine do use photographs of the tomb but only a standard view.

There is simply no image of the baoli or other building that became the object of popular gaze or veneration in commercial circulation. A curiosity for such a popular image arises (for this study) since posters called naqshas giving rough cartographic details of pilgrimage centres such as Ajmer have been in circulation in the 20th century.

While the titles of some of these Urdu books show a standard

photo or illustration of the shrine building, some also decorate

such ordinary images with embellishments, just as in the

devotional posters, to communicate their devotion to the saint.

While the titles of some of these Urdu books show a standard

photo or illustration of the shrine building, some also decorate

such ordinary images with embellishments, just as in the

devotional posters, to communicate their devotion to the saint.

Nizamuddin shrine has enough venerable sites (even if clustered

in a small area) such as Amir Khusrau’s tomb,

hujra-e qadeem (the ancient room),

langar khana (hall for community food), baoli,

urs mahal (concert stage for qawwalis),

taaq-e buzorg (an ancient niche), chilla sharif

(saint’s meditation room) and so on, some of which a pilgrim is

supposed to visit ritually for specific ceremonies, especially

during the annual urs of the saint.

Nizamuddin shrine has enough venerable sites (even if clustered

in a small area) such as Amir Khusrau’s tomb,

hujra-e qadeem (the ancient room),

langar khana (hall for community food), baoli,

urs mahal (concert stage for qawwalis),

taaq-e buzorg (an ancient niche), chilla sharif

(saint’s meditation room) and so on, some of which a pilgrim is

supposed to visit ritually for specific ceremonies, especially

during the annual urs of the saint.

None of these are pinpointed in any available map, although the

regular visitors roughly know their location and importance. One

could infer that none of the mass-produced images of Nizamuddin

shrine discussed so far have the scope of invoking the sacrality

of the buildings or archetypes, the way they do for instance in

the devotional images showing Ajmer or other shrines (except the

poster showing the assembly of six Sufis, whose depiction of the

Nizamuddin’s tomb is more imaginary than accurate).

None of these are pinpointed in any available map, although the

regular visitors roughly know their location and importance. One

could infer that none of the mass-produced images of Nizamuddin

shrine discussed so far have the scope of invoking the sacrality

of the buildings or archetypes, the way they do for instance in

the devotional images showing Ajmer or other shrines (except the

poster showing the assembly of six Sufis, whose depiction of the

Nizamuddin’s tomb is more imaginary than accurate).

More importantly,

the baoli which was once considered as important as the tomb

itself was left to rot as a sewage tank and a ruin, symbolically

as well as physically. Its previously perceived symmetry and

arches got completely lost in the maze of new concrete

additions.

the baoli which was once considered as important as the tomb

itself was left to rot as a sewage tank and a ruin, symbolically

as well as physically. Its previously perceived symmetry and

arches got completely lost in the maze of new concrete

additions.

1. Lowry, Glenn D., "Delhi in the 16th Century," Environmental Design, Journal of the Islamic Environmental Design Research Centre, 1984, 7-17. 2. Koch, Ebba, Shah Jahan's visits to Delhi prior to 1648: new evidence of ritual movement in urban Mughal India, In Mughal Architecture: Pomp and Ceremonies, Environmental Design 1991, 1-2:18-29. 3. Ibid. Lowry, 1984, p 11. 4. Anjum, Khaliq (ed.), Asar-us Sanadid by Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan, 2nd edition, 1853. 5. This album is available in the British Library, London. 6. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/addorimss/t/019addor0005475u00043vrb.html 7. Nizami, Khaliq A., Shaykh Nizamuddin Aulia (Urdu), New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1998, p 25. 8. Ibid. Nizami, 1998, p. 77-78. 9. Preserved in the British Library, UK. 10. http://www.gerty.ncl.ac.uk/photos_in_album.php?album_id=19&start=270 11. Produced by D. Macropolo & Co., Calcutta. 12. "Let nothing but green grass cover my tomb/ For it is the best grave cloth of poor in spirit. The humble and mortal Jahanara Begum. (Believer of Chishty Family.)" 13. Pinney, Christopher, Photos of the Gods, Reaktion, London, 2004, p 14. 14. Ibid. Nizami, 1998, p. 77-78